Antoni Gaudí, a style of his own

Gaudí was a very unique architect.

The many contradictions in his work make it difficult to pigeonhole him into a specific architectural style, trend or avant-garde movement, as has so often been attempted.

What we do know, however, is that his new, unique, versatile and evolutionary style broke with the past and was several years ahead of any other of the avant-garde European movements of the time, and radically transformed the architecture of his day by way of three main techniques: the use of colour, a combination of different materials and the incorporation of movement through the use of geometry.

Despite all this, his style is generally categorised as belonging to Catalan Modernisme (an offshoot of Art Nouveau) – a movement that coincided with his most profuse creative period, in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Background and childhood

Antoni Gaudí was born on 25 June 1852, in the county of Baix Camp (some biographers say in the city of Reus, while others place him in Riudoms – more specifically at the Mas de la Calderera country house).

His father, Francesc Gaudí Serra (1813-1906), was a boilermaker, and his mother, Antonia Cornet Bertran (1813-1876), also hailed from a family of the same trade. Over five generations of craftsmanship had imbued Gaudí with a great capacity for spatial conception, and the ability to perceive the plastic qualities of a design, before it was projected onto a flat surface.

As an infant, Gaudí suffered from rheumatism. The disease often kept him away from school, as a result of which, during his long stretches of solitude, he developed great skill as an observer of nature.

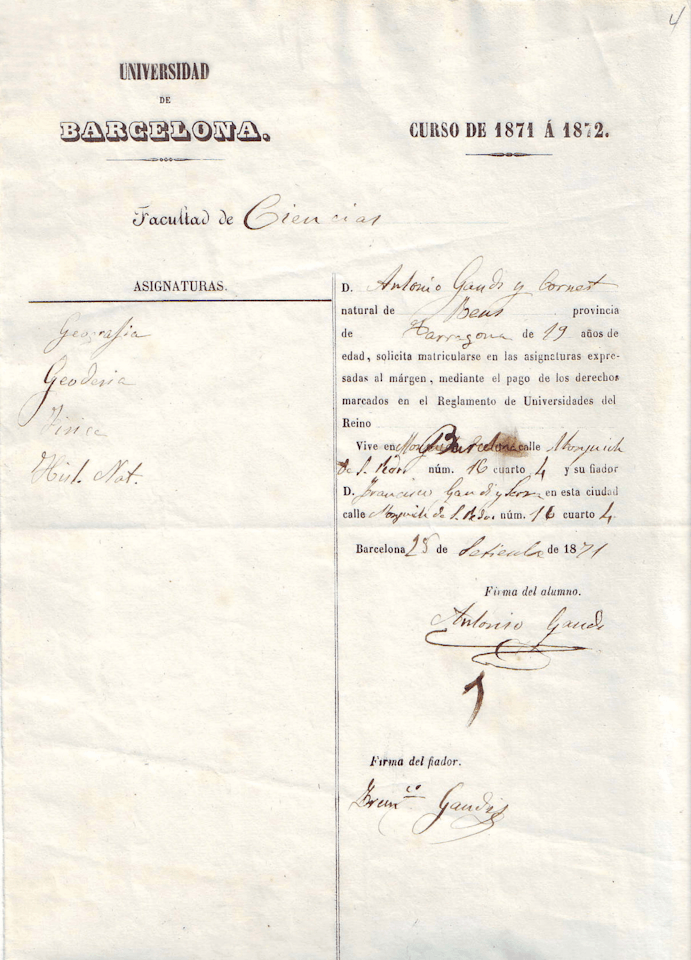

Gaudí, the architecture student

His first years of schooling took place in Reus, at the nursery run by Francisco Berenguer (the father of his friend and collaborator Francisco Berenguer Mestres), and then at the school at Reus Hospital, presided by Rafael Palau.

In 1863, he enrolled in the Escolapis de Reus school, where he received the religious and humanist instruction typical of the Saint Joseph of Calasanz Order. He attended this school until the 1868-1869 academic year, when he then moved on to do the Baccalaureate at the Institut d’Ensenyament Mitjà in Barcelona.

While at university, he became a dedicated enthusiast of the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, pouring over each new book that came into the School’s specialised library. He also had a profound interest in photographs of Greco-Roman, Arabic and Byzantine art.

While at the School, he combined his studies with his job as a surveyor for the architects Francisco de Paula Villar and Josep Fontserè.

Gaudí’s marks as an architecture student were inconsistent. He graduated on 4 January 1978, with a “pass” for his final assessment, for which he had to design a university auditorium. This was a daunting task, given that the head of the examining panel was Elies Rogent – also the School’s headmaster – who had created the auditorium for the University of Barcelona some years previously.

When awarding Gaudí his architecture degree, Rogent uttered the now-famous words: “We’ve awarded this degree to either a genius or a madman, only time will tell”.

Gaudí left behind very few written records of his architectural theories. The two most substantial of these are a study on ornamentation, and La casa pairal, both written upon completing his studies and now held at Museu de Reus.

Gaudí’s works

Gaudí’s architectural career began with a commission from Barcelona City Council to design a set of streetlamps for the Plaça Reial and the Pla de Palau, followed by the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense (the “Mataró Worker’s Cooperative”) – a project that was never completed.

His first major commission was for Casa Vicens – which was also his first house. This work marked the beginning of his Oriental period, and the house is steeped in his knowledge of Arab architecture. We can also identify traces of his studies of photographs from Egypt and India, Moorish Spanish monuments, and influences from the book The Grammar of Ornament (1856), by Owen Jones.

Gaudí’s death aged 73

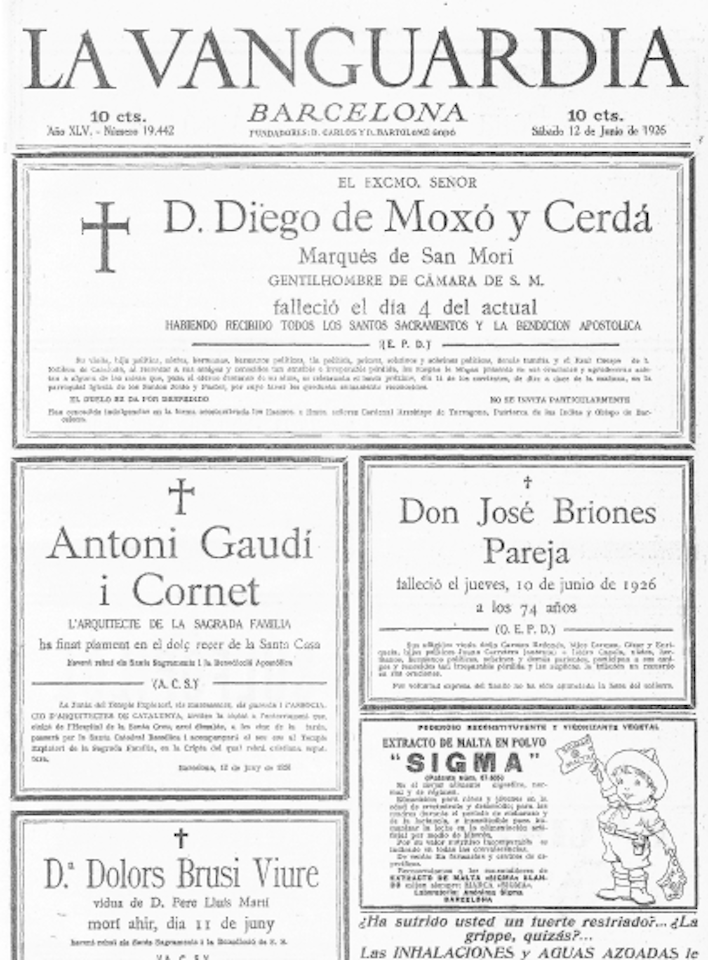

On 7 June 1926, and on his daily walk to the Sant Felip Neri oratory for vespers, Gaudí was hit by the Line 30 tram, at the intersection of Carrer de Bailèn and the Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes.

Due to his humble appearance, nobody recognised him at first – not until he was given first aid and taken to the former Santa Creu hospital, located in the neighbourhood of El Raval. The architect was in a critical condition and died at the hospital on 10 June, three days later.

On 12 June thousands of people joined a cortège from Santa Creu hospital to the Sagrada Família, where his funeral took place.

Barcelona took to the streets to bid the great architect goodbye. Numerous black mourning crapes hung from the city’s buildings, as a final farewell to Antoni Gaudí. The press of the time described the scene as a “great outpouring of grief”. The procession marched to the Sagrada Família’s crypt at the back of the cathedral, where his tomb is now located.

Gaudí’s inner circle

Antoni Gaudí’s majestic works must also be recognised for the craftsmanship they entailed. Here are the most significant figures who propelled and collaborated on Gaudí’s works:

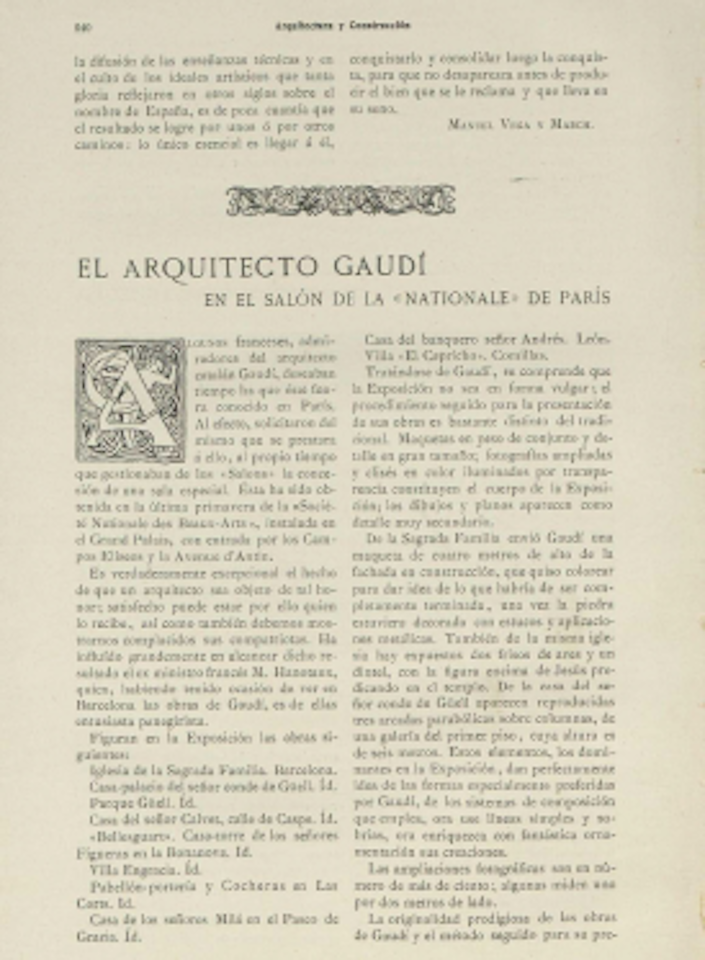

In life, Gaudí was the subject of only one exhibition, that took place from the 15 April to the 30 June 1910 at the annual salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (National Society of Fine Arts) at the Grand Palais in Paris.

Some of the exhibition’s pieces included: models of the Sagrada Família; a painting of Casa Vicens by Aleix Clapés; a plaster-of-Paris reproduction of the arcade of the gallery at Palau Güell; and numerous photographs taken by Adolf Mas of buildings patronised by Eusebi Güell, who also financed the exhibition.

Multiple reviews of the exhibition were published in the French press, but reactions were mixed – and the show was met with both “enthusiastic praise and criticism” at once (La Vanguardia, 12 May, 1910).

The next exhibition of note to feature Gaudí’s work took place from 1936-1937 at MoMa (New York). Entitled Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, the show included 10 photographs featuring the Sagrada Família, Park Güell, Casa Batlló and La Pedrera, which were displayed in the “fantastic architecture” section.

Two decades later, in 1956, an exhibition took place at the Saló del Tinell (Barcelona), organised by the Associació Amics de Gaudí (the Friends of Gaudí Association).

The MoMA (New York) paid renewed homage to the Catalan architect with the exhibition The Architecture of Gaudí (18 December 1957 - 23 February 1958), organised by Georges R. Collins and Josep Lluis Sert and curated by the architecture historian Henry-Rusell Hitchcock.

In the 1970s, from 18 June to 27 September 1872, at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, an exhibition on Gaudí was held as part of its Pioneers of the 20th Century programme. The show was organised by the Associació Amics de Gaudí and the Càtedra Gaudí research and documentation centre of the Barcelona School of Architecture. It was financed by the French government and welcomed over 30,000 visitors.

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of Gaudí’s birth, 2002 saw the International Year of Gaudí, an event curated by Daniel Giralt-Miracle which – as he professes in his book, Essential Gaudí – signified “the definitive recognition of Gaudí’s work”, and “an approach to his buildings that goes further beyond his façades and their poster and postcard images”.

In this same year, countless exhibitions devoted to architect took place, some of which included: 'Impacte Gaudí', held at the Santa Mònica Arts Centre; 'Gaudí. Art and Design', in La Pedrera’s exhibition room; and 'Dalí and Gaudí: The Revolution of the Sentiment of Originality', held at both the Gala-Dalí Castle in Púbol and the Centre of Contemporary Culture (CCCB) in Barcelona.

In 2021, the exhibition 'Gaudí' was inaugurated at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC, Barcelona), curated by Juan José Lahuerta. In 2002, the same exhibition was repeated at the Musée d’Orsay (Paris, France). The exhibition offered a new perspective of the architect and his work through more than 650 pieces.

In addition to these exhibitions, the 1950s was also a significant decade, in which numerous events aimed at resurrecting the figure of Gaudí took place, sparked by the 100th anniversary of his birth. These included:

· The creation of the Friends of Gaudí Association by César Martinell, the first initiative in Spain to bring the architect back onto the public stage.

· The creation of the Friends of Gaudí Association in Japan, founded by the architect Kenji Imai.

· The creation of the Càtedra Gaudí research and documentation centre at the Barcelona School of Architecture in 1956, with Josep Francesc Ràfols i Fontanals as its first director.

· A lecture by Salvador Dalí at Park Güell in 1956: a homage in which Dalí gave a speech and painted the outline of the Sagrada Família in tar, upon an immense, 6 metre-high canvas that was aimed at raising funds for the cathedral.

· The launch of Gaudí onto the international stage in a text by Josep Lluís Sert, accompanied by photos by Joaquim Gomis and Joan Prats, which was published in the “Fotoscops” collection.

· In 1956, George R. Collins visits Barcelona and the Gaudí exhibition at the Saló del Tinell. He subsequently creates an offshoot of the Friends of Gaudí Association in New York, and publishes the first English-language study of the architect in 1960.

The next major recognition of Gaudí’s architectural work took place in 1984, when – for the first time – some of his works were declared Unesco World Heritage Sites: Casa Milà, Park Güell and Palau Güell.

In 2005, this designation was extended to include: Casa Vicens, Casa Batlló, the Church of Colonia Güell, and the Nativity Façade and crypt of the Sagrada Família. A total of seven buildings distinguished for Gaudí’s exceptional contribution to the evolution of architecture and his revolutionary building techniques.