Gaudí’s original project (1883-1885)

Casa Vicens is the first major commission that Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) received, a prelude to his entire subsequent architectural work. It is his first masterpiece and one of the first buildings that launched Modernisme in Catalonia and in Europe.

Until then, Gaudí had only worked on smaller projects, especially urban development projects, as he was finalising his studies in architecture.

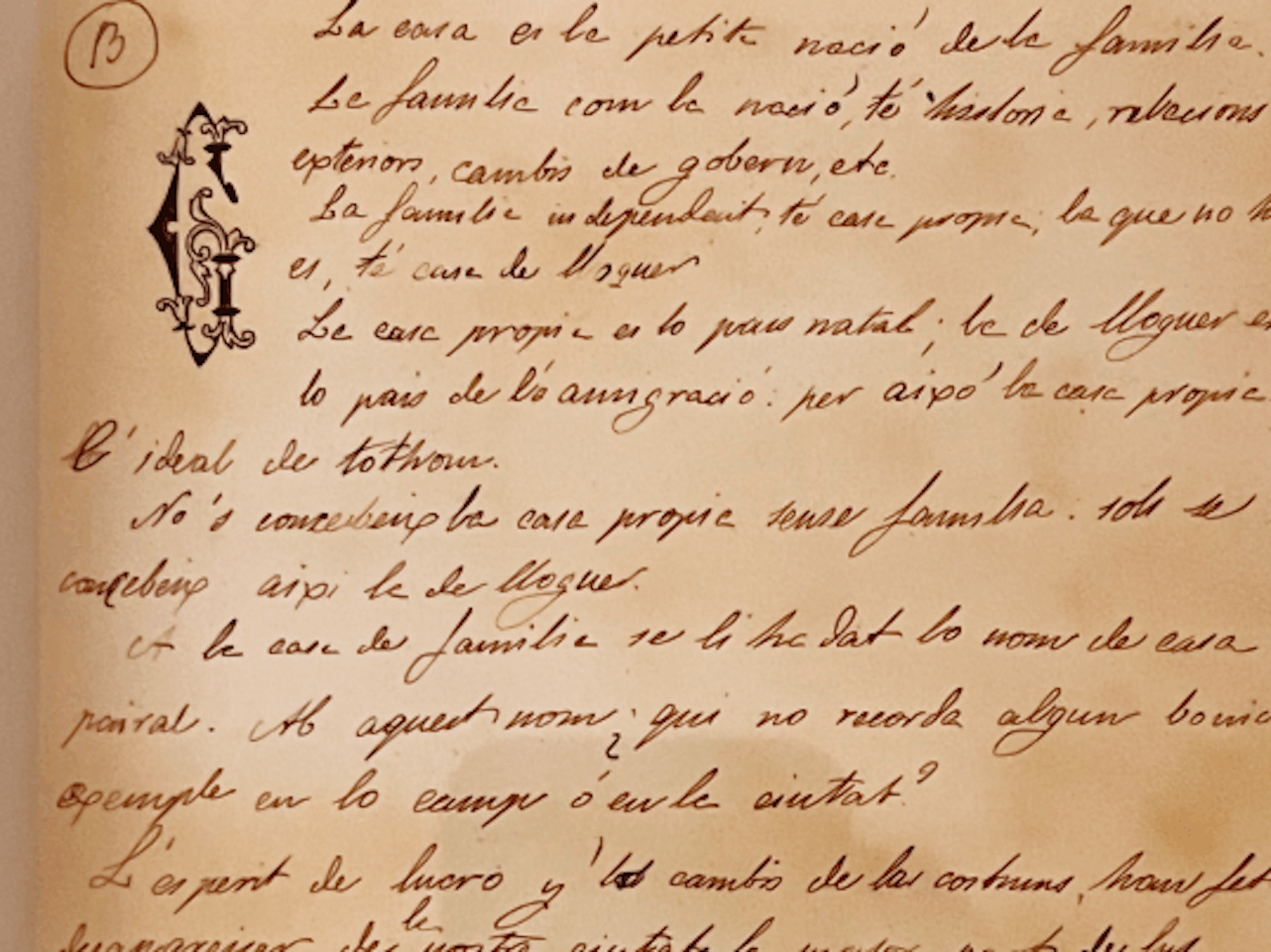

Casa Vicens is the first home designed by Gaudí. This single-family home was designed under the precepts that he wrote in the document known as “The manor house” (1878-1883).

In the document, Gaudí reveals the importance of the home as the family’s tiny nation and it must be oriented to have the greatest amount of light and ventilation possible.

Gaudí remarked on the one hand the hygienic conditions that a house must have so that people living in it grow up to be strong and robust. Likewise, the artistic conditions must forge character, so that the children born there become the true children of the stately home.

With these premises in mind, Gaudí, a young architect having barely turned 30, designed Casa Vicens. This building is considered his manifesto, as it is the space where the architect gave shape to these ideas and started to reveal his immense talent.

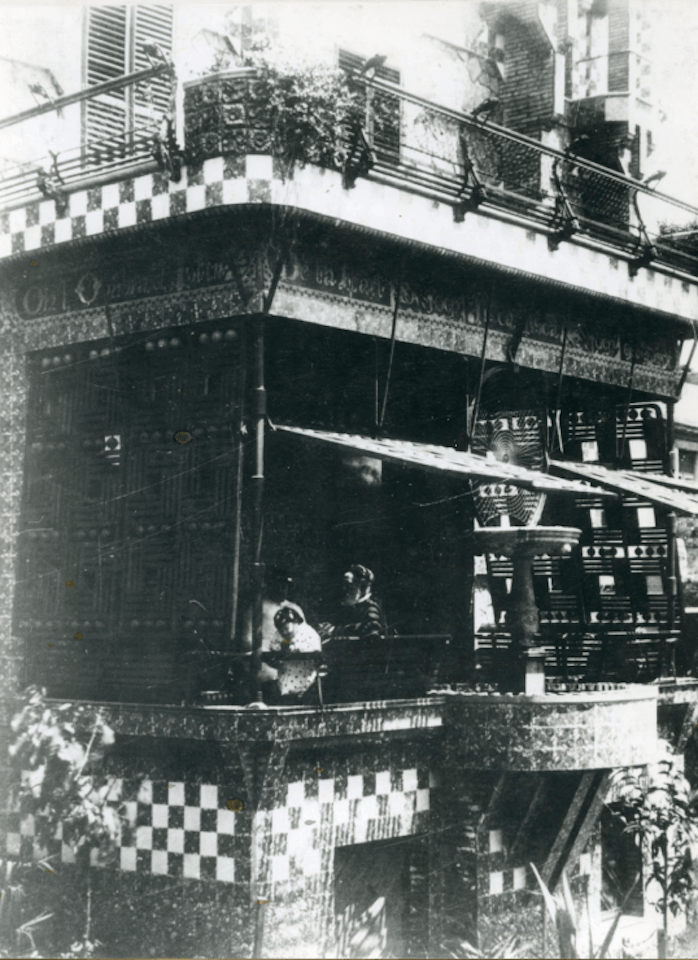

As a starting point to his work, Gaudí created an innovative, original piece that stood out from what had previously been built in Catalonia. Casa Vicens is one of the first examples of the rejuvenated aesthetics and architecture that took place throughout Europe in the late 19th century.

The construction of Casa Vicens is located in the village of Gràcia, a town that until the 19th century was agricultural and sparsely populated. However, with the industrial revolution, steam factories started to take root which accelerated urban expansion turning Gràcia into a town with excellent cultural, worker and petit-bourgeoisie activity. Around 1860, the village had already established the street pattern that has lasted more or less to our days.

Gran de Gràcia was an extremely important street, the path that connected to the aristocratic Passeig de Gràcia, which in turn acted as the central axis and the main connection between Barcelona and the burgeoning town of Gràcia. The tramway reached the port which made it possible to bring the two towns closer together.

Finally, Gràcia was annexed as a new neighbourhood to the city of Barcelona in 1897.

The commission from Manel Vicens

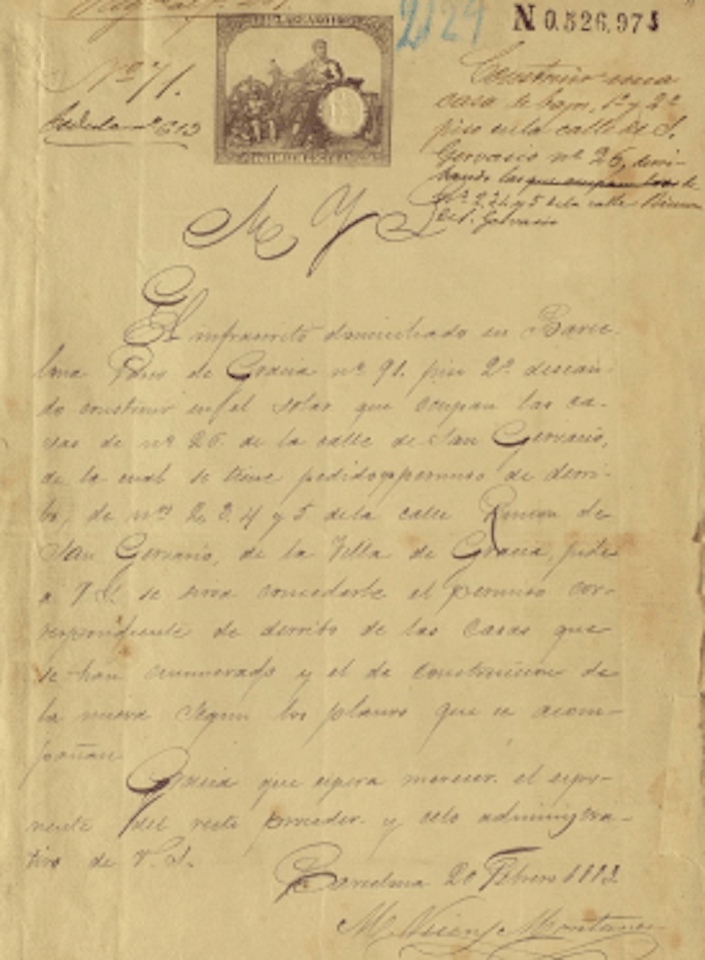

The origin of the commission for Casa Vicens takes us back to 20 February 1883, the moment when Manel Vicens i Montaner requested permission from the Vila de Gràcia Town Council to build a summer home on no. 26 Carrer de Sant Gervasi street, now known as Carrer de les Carolines.

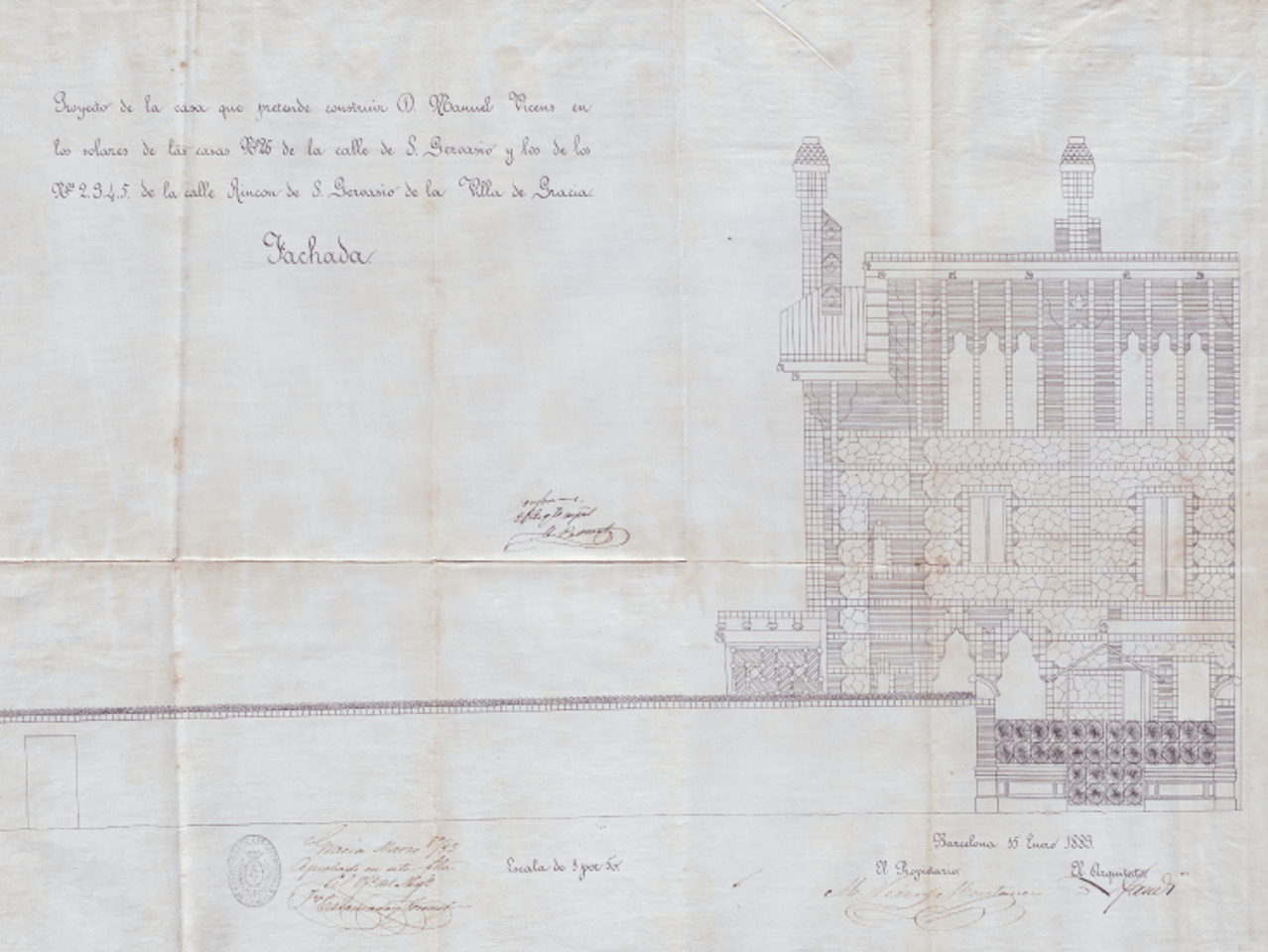

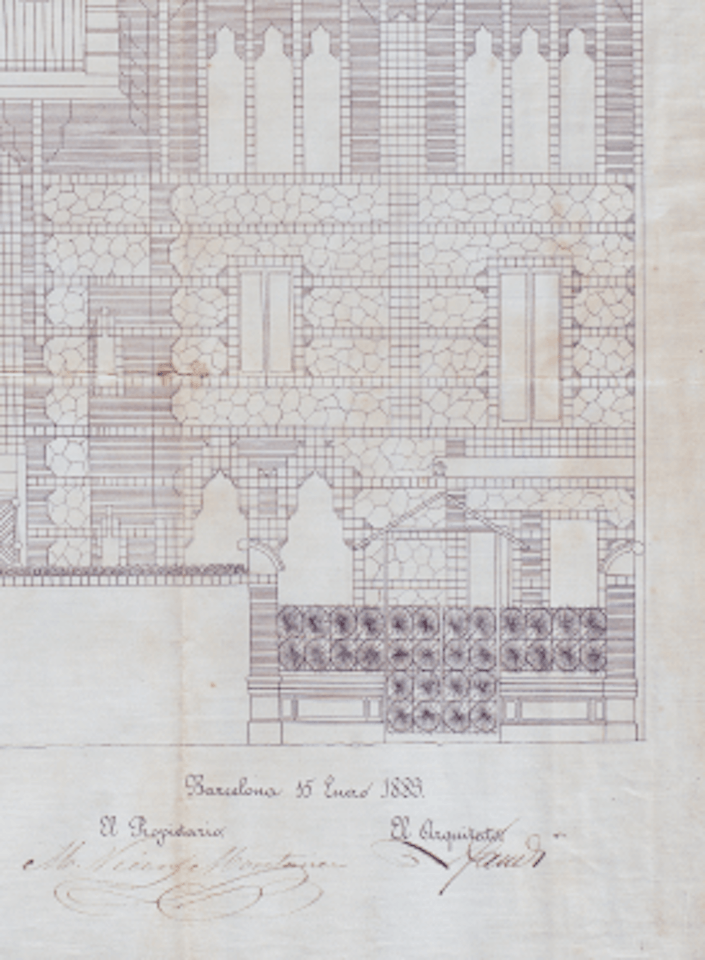

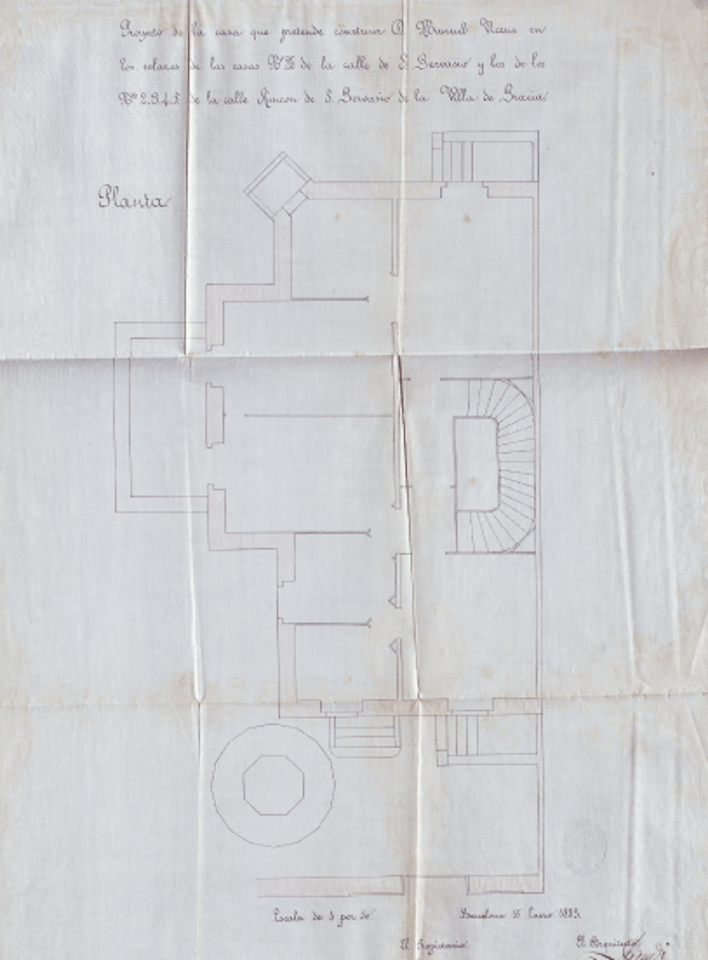

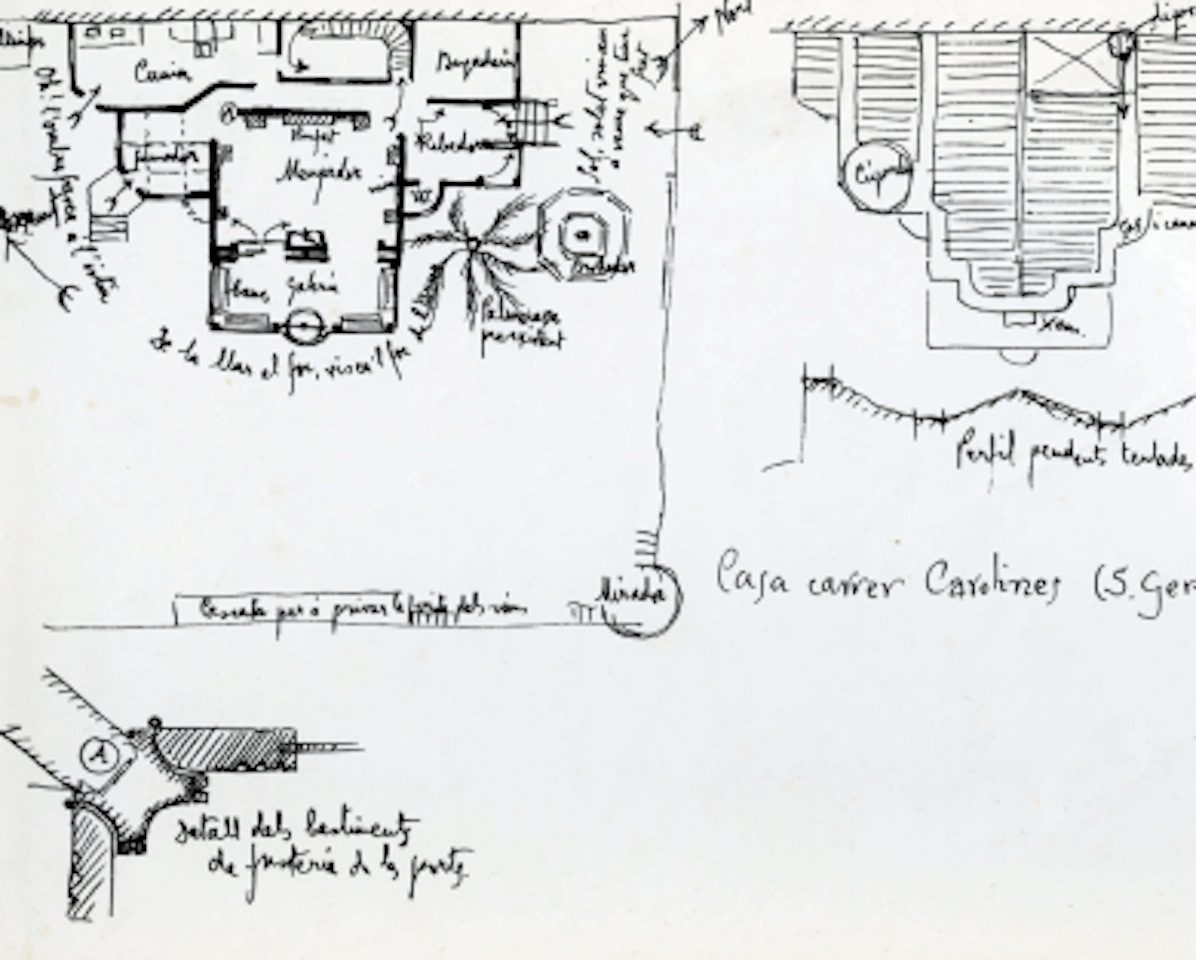

One month before Vicens had requested permission to raze the house that he had inherited from his mother, Rosa Montaner, since it was in rather poor condition. The requested was accompanied by a series of four plans (location, floor plan, elevation and section) signed by the architect Antoni Gaudí, dated 15 January 1883, where we can see his immense creativity and design skills already on display.

In the ink drawing of the façade, we can see how Gaudí meticulously delineated the leaves of the palm tree that would be placed on the grille at the entrance. The sculptor Lorenzo Matamala was commissioned to create the piece and was cast by Joan Oñós.

In the plans submitted to the city council we can see how Gaudí’s construction included three façades attached to a party wall with the neighbouring construction. The southwestern façade, the main one, remained open to the large garden that surrounded the house.

The orientation and the lush plant growth in the garden ensured that the summer house remained fresh and cool. The garden was also structured in two spaces: one with circular flowerbeds in front of the main façade, and another dedicated to the vegetable garden, located higher up, at the back of the plot.

Manel Vicens (1836-1895)

At present, no documentary source has been located which shows a direct link between Gaudí and Manel Vicens. Based on certain documents, the hypothesis is that Manel Vicens and Antoni Gaudí frequented similar associations and entities in Barcelona at the time. Through these associations, whether directly or indirectly, Vicens and Gaudí came into contact until the commission was formalised.

A great number of people met around the Renaixença, the Centre Català, the Ateneu Barcelonès and the Associació Catalanista d’Excursions Científiques, ranging from magnates like Eusebi Güell to writers, architects and artists, such as Francesc Torrescassana, Mariezcurrezna, and more, all of whom were subsequently linked to Gaudí’s work and also to Casa Vicens.

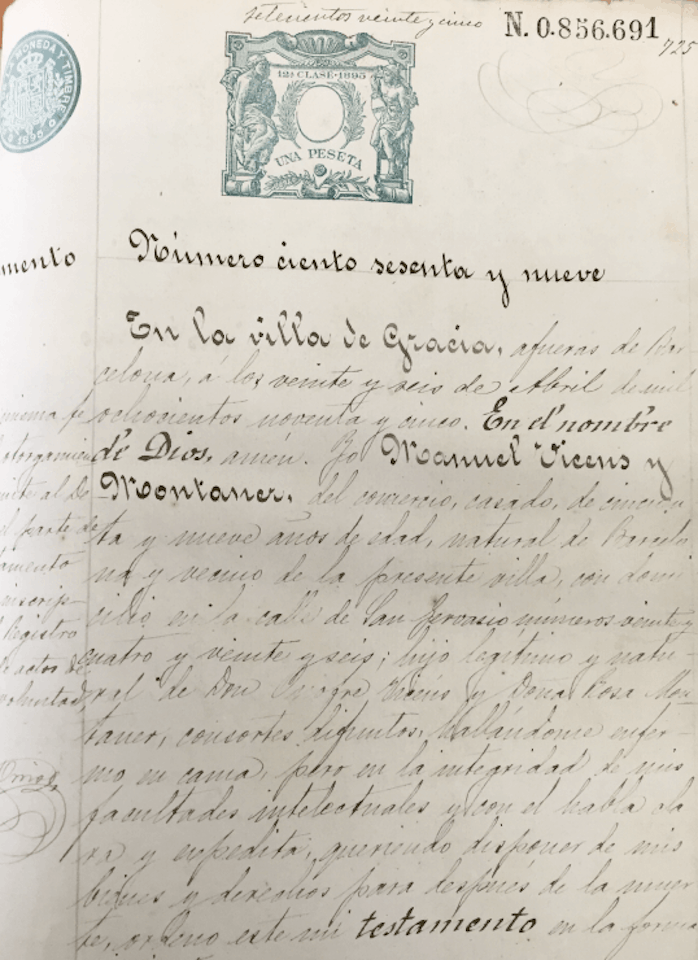

We know very little of Manel Vicens (1836-1895). The last will and testament of Manel Vicens is the most notable document to understand him. In it, he stated that his profession was a stock and currency broker.

Through the inheritance from his mother, Rosa Montaner y Matas, Manel received the land on what is today Carrer de les Carolines, then known as Carrer de Sant Gervasi, and he enlisted Gaudí to build a second residence on that plot in order to spend his summers in the town of Gràcia.

Mrs. Rosa Montaner y Matas indicated in her will that all her assets came from Agustín María Baró y Tastas, who named her his sole heir upon his death.

Manel Vicens passed away in 1895, leaving his wife, Dolors Giralt i Grífol, as his sole heir and, in the case of her death, their daughter Juana Peña Medina. Juana was originally from Alhama and was adopted by the Vicens family at the tender age of five after being orphaned by the earthquake that levelled the town in Granada on 25 December 1884.

Manel Vicens’s will also mentioned a house in the town of Alella, for which Gaudí designed two pieces of furniture that can be seen in the permanent exhibition, as well as two properties in the centre of Barcelona and some land in the area of Vallvidrera.

Four years after Manel Vicens’s death (December 1899), his widow sold the house to Antonio Jover Puig for 45,000 pesetas, as recorded in the Property Record.